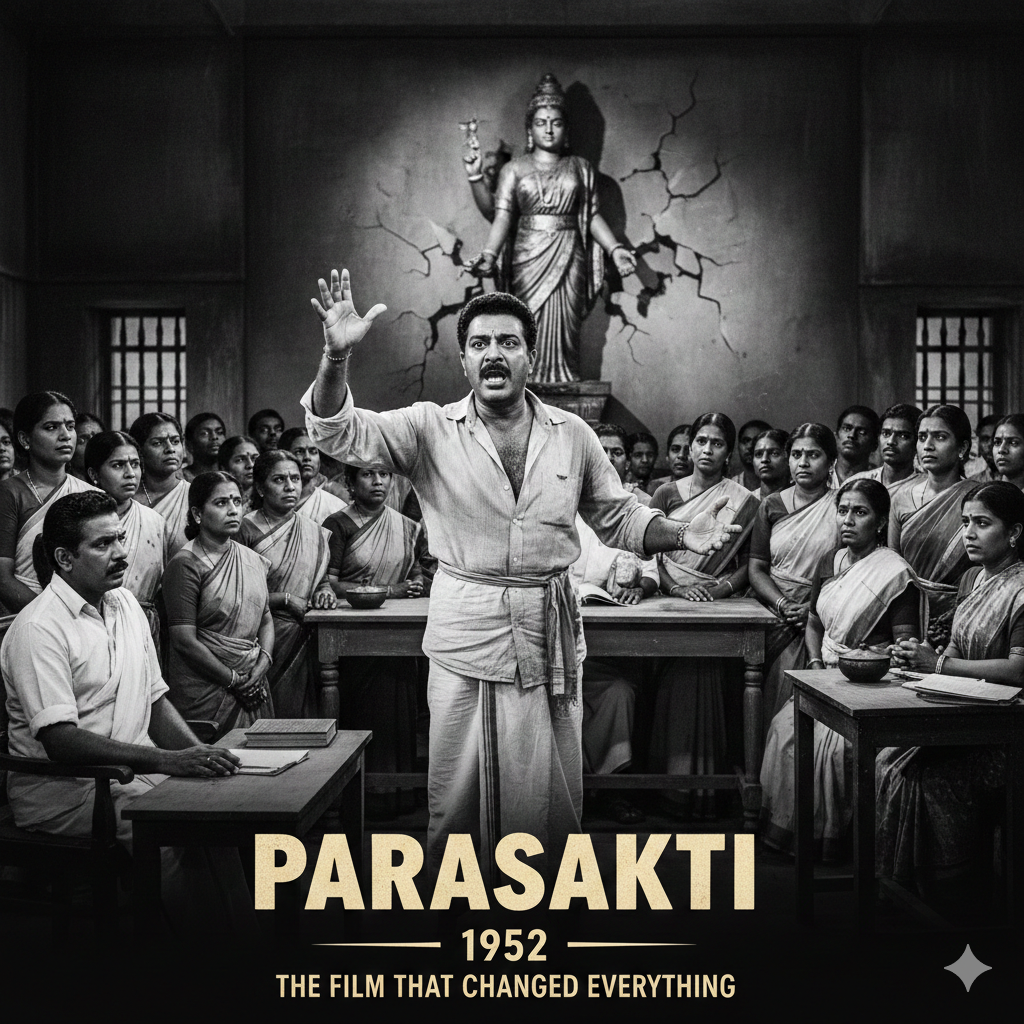

Parasakti: The Film That Changed Everything

Karunanidhi is not subtle at all about infusing Dravidian pride into Parasakti. He sets the stage very early on when a performer sings, "Valama Enadhu Dravida Naadu Vazhagave" (Long live my prosperous Dravidian land). The song proudly mentions Telugu, Malayalam, and Kannada, while giving Tamil a special status. As the song ends, a character graces the stage to lament the plight of Tamils in countries like Sri Lanka and Rangoon. This is where you find the first instance of Karunanidhi’s imaginative writing: "If you ask why the sea water is salty, a poet would say it is the tears shed by those who couldn't survive in their own land."

Parasakti is the story of a family whose lives are infused with knowledge and inspiration after facing poverty and sorrow. This applies particularly to Gunasekaran, played so effectively by Sivaji Ganesan that it is hard to guess his actual age. It is the story of a man who enjoys the luxury of coffee in bed—“Thambikku suryodayam paarkradhu pidikadhe” (Brother doesn't like watching the sunrise)—but when fate deals him a foul blow, he realizes how few people are actually entitled to such freedom. As the beautiful Pandari Bai says, "If you weren't born into poverty, you wouldn't have even thought about the world of the poor."

This is one of the film’s many sharp dialogues, and one of the many instances where characters suddenly switch from everyday Tamil to literary Tamil. This is how Karunanidhi makes his point, highlighting his repeated expressions of love for the language. In one song, a girl expresses her attraction to her lover by saying, "Kanivana mozhiyil ennai kavarandhire" (You have captivated me with your sweet language).

How wonderful it is that a woman is attracted to a man because of his conversational ability—not his physical appeal, beauty, or fighting prowess, but because of how beautifully he weaves words. Karunanidhi included some very interesting women in this film and navigated past many common tropes.

When pregnant Kalyani’s father expresses a wish for a baby boy and the parents decide to name him Panneerselvam, his son-in-law jokingly says, "Pen pirandha Nagamma nu theermanam pannirukom" (If it's a girl, we've decided on Nagamma). This 1952 film also features a woman who poisons Gunasekaran’s drink.

I also love that it is a woman, played by Pandari Bai, who makes Gunasekaran realize his selfishness. It is through her that Karunanidhi signals that revolution is the need of the hour: "Social growth isn't about cutting the branches; it’s about uprooting the foundation."

It is not hard to understand why the dialogues of this film are still so praised today. Karunanidhi reaches his peak when Gunasekaran and his family's situation turns dire. Once again, he does not hesitate to unleash havoc on the family. Kalyani's husband dies in a ridiculous accident. When her father finds out, he also dies of shock in an almost farcical manner. You can see Karunanidhi "removing" people from the path to analyze poverty and society's reaction to it. In a way, the words of a stranger at the beginning foreshadow all these terrible events: "Innum ena laam aaga pogudho" (Who knows what else is going to happen).

Once Karunanidhi has spread death and disaster over Gunasekaran’s family, his writing truly comes to the party. Kalyani, unable to manage food for herself and her infant, sings: "Had you been born in a bird's nest, food would have flown to you to quench your hunger. Oh, you are born in a land where millions of poor wither while the wealthy flourish." The description often bursts with imagination, such as when Gunasekaran explains how the poor are neglected: "Instead of a horse, a man pulls a rickshaw until his nerves pop. He sleeps on the pavement with his family curled up like a dog. I am talking about a human who has been turned into a four-legged animal."

The film repeatedly suggests that death is better than living in poverty. Gunasekaran says, "Leaving someone to live in poverty is the real sin." His sister Kalyani eventually attempts suicide. This idea of death as a last resort brought to mind scenes from the climax of Naan Kadavul. In this sense, watching Parasakti today reminds one of scenes from many contemporary Tamil films. When Gunasekaran first arrives in Chennai, his car is surrounded by beggars.

I was reminded of a similar scene in Rajinikanth's film Sivaji. Shankar's Sivaji is also the story of a rich man who becomes penniless and then fights for the upliftment of the downtrodden. Perhaps then Rajinikanth's famous dialogue—"Parasakti hero da!"—could have meant something more than just a catchphrase. Another scene where Gunasekaran turns on a tap and no water comes out reminds me of that famous Vivek joke in the film Run.

Regarding the film's politics, it is hard to ignore Karunanidhi's unpleasant portrayal of migrants, especially those shown speaking Hindi or distorted Tamil. When a Hindi-speaking Tamil person apologizes, he is interrupted: "Maaf karoji or whatever, to hell with your 'karoji'." In another scene, Gunasekaran is begging a Marwari businessman for money to go to Madurai. The businessman replies, "You go Bombay, you go Madurai. What is it to me?" The portrayal of Brahmins in the film is also not particularly favorable, as they are mostly shown as cowardly and malicious. The priest who attempts to molest Kalyani is a vivid example of this.

In a film made on such serious subjects, Karunanidhi's humor provides some brilliant scenes. When a policeman wakes Gunasekaran—who is sleeping on the footpath—by splashing water on him, he calmly asks for soap because he hasn't washed in a long time. Even funnier is the exchange: Policeman: "Why are you staring?" Gunasekaran: "What else is one supposed to do when you wake a sleeping man?" Policeman: "You’re a pickpocket, aren't you?" Gunasekaran: "No, just empty pockets."

It is hilarious, as is the scene where Gunasekaran steals murukku. Karunanidhi’s fiery lines benefited greatly from Sivaji Ganesan’s delivery.

Karunanidhi’s atheism is also a hallmark of his writing. There is a constant mockery of God’s apparent inability to intervene and save the day. When Gunasekaran steals fruit and the vendor prays to God, he says, "God didn't listen. His heart has turned to stone." In a more famous scene, Gunasekaran dramatically emerges from behind a goddess idol, saying, "When has the Goddess ever spoken?" The irreverence could not be clearer. Karunanidhi also seeks to expose the hypocrisy of seemingly great believers whose actions suggest otherwise, as when Gunasekaran questions the priest: "Parasakti is a mother to you, but my sister is a servant (dasi) to you?" Further evidence of the ridicule of rituals appears when a priest chants, "Om kreem kreem yung mung gao."

You also realize that Mahanadu used to be a favorite word back then. Fittingly, the film ends with a Mahanadu (a grand conference); a ceremony featuring visuals of Karunanidhi, Periyar, and Anna. Anna is mentioned much earlier in the film when Pandari Bai's character is asked how she became so educated and socially aware. She says, "Ellam Anna dhaan" (It's all because of Anna), and then starts talking about her brother. However, this film belongs entirely to Karunanidhi. And as long as this film remains relevant, the artist within Karunanidhi will live on.

Comments

Leave a Comment